Since my wonderful grandmother was unable to post each day, I have started adding news articles to add a little interest. While searching for what happened 80-years-ago I found this amazing article on Page 3 of the Atlanta Constitution from March 22, 1914.

The story of Ditty being born on the train as the family escaped from Mexico was retold many times. Little did I know it made a full page article. Click on the PDF to see the article and all the great pictures. The_Atlanta_Constitution_Sun__Mar_22__1914_

I have done my best to transcribe this article for you!

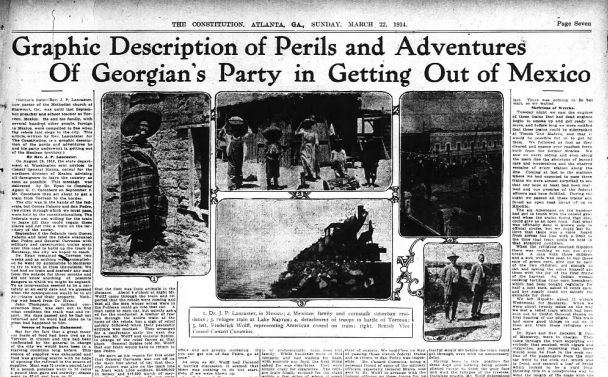

(Editors Note- Rev. J.P. Lancaster, now pastor of the Methodist church at Shawmut, Ga. Was until last September preacher and school teacher at Torreon, Mexico. He and his family, with several hundred other people foreign to Mexico, were compelled to flee when the rebels laid siege to the city. This article, written by Rev. Lancaster for The Constitution is a graphic description of the perils and adventures he and his party underwent in getting out of the Mexico territory.)

By Rev. J.P. Lancaster

On August 26, 1913, the state department at Washington sent advices to Consul General Hanns, Consul for the northern division of Mexico, advising all foreigners to leave the country as soon as possible.

This message was delivered by Dr. Ryan to Consular Agent G.C. Corothers on September 1. Mr. Corothers then set about to get a train from Torreon to the border.

The city was in the hands of the federals, but Gomez Palacio and San Pedro, two cities through which we must pass, were held by the constitutionalists. The federals were not willing for the train to leave till they could regain these places and not risk a train on the territory of the enemy.

September 6 the federals took Gomez Palacio and later the rebels evacuated San Pedro and General Carranza with military and construction trains went over this road to build up the track to Monterrey, the city we hoped to reach.

Dr. Ryan remained in Torreon two weeks and as nothing was accomplished he went by automobile to Monterrey to try to work from the outside. We had had no train and scarcely any mail from the outside for three months and did not know anything of possible dangers to which we might be exposed. To us intervention seemed to be a certainty at an early date and we guessed what the consequences would be to all Americans and their property. Nothing was heard from Dr. Ryan.

John Thompson, a railroad constructional man, was sent out to find what condition the track was and report. Six days passed and he had not returned and no word had come as to what happened to him.

Source of supplies exhausted.

But for the fact that a great many car loads of food had been laid up in Torreon in transit and this had been confiscated by the general in charge of the the city we would have been in a starving condition long before. This source of supplies was exhausted and food was growing scarce with no hope of opening the railroad to the source of supplies. Meat was 75 cents a pound, lard $2 a pound, potatoes went to 50 cents a pound then gave out entirely; cheese went to $2.40 and ham to $2.

The banks were out of money. The Laguna bank turned down a check for $500 made by John Brittingham, a multimillionaire who was president of the bank. They said, they could give a check that would be cleared at any bank in the world, but then did not have the money. The Mexican government, in order to pay the soldiers, had demanded that the banks use their reserve gold supply to supply the army. Money was out.

At least three dates had been advertised as the time when the refugee train would leave during the twenty-two days of waiting. The last disappointment had so stirred the Americans that another postponement would have brought serious trouble. The United States government had said twenty-four days before “Get out at once.” and we were still there, being put off by the officials of the federal government.

When all was in readiness to depart the next morning we confronted a new difficulty. While the Americans were in the American bank, Mr Barrett, the bank president, was heard to say “There will be no train tomorrow.” Mr. Corothers was seen in the bank and when asked what the statement meant said that there would be no train unless he could raise $5,000 that night. A dissatisfied depositor, an American, had withdrawn all his money that day and the bank did not have the money to pay for the train. This deficit was met in some way, however, by Mr Corothers and the next day, September 15, the train was ready to carry 350 foreigners to the border.

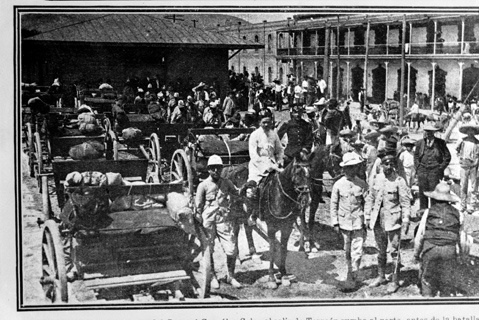

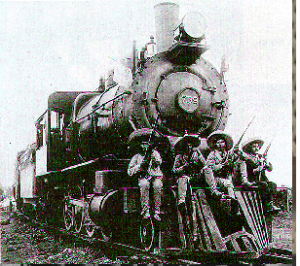

On Thursday September 21, we left Torreon at 11 o’clock with a train of thirteen cars consisting of two water cars, two cars of wood for the engine, one second-class car for food and cooking, two baggage cars, five first class passenger cars and one Pullman. An American negro was in charge of the engine and Frederick Wolff was appointed by Consular Agent Corothers to have the entire charge of the train as his representative.

We stopped at Gomez Palacio, 3 miles from Torreon, where we took on two more cars, one of which was full of nuns of the Romanist school there, all in uniform. We left Gomez at about 11:30 o’clock and went without delay to San Pedro 50 miles.

Bridges Burned

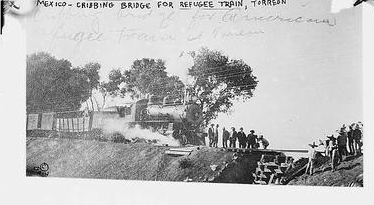

When we reached San Pedro we learned that a train had been sent by the Mexican government over the line to see what condition the road was in. This train returned Friday morning and reported that they found two burned bridges and a washout.

Found on revolucionentorreon.galeon.com

Saturday morning a construction train came from Torres with instructions to pick up a part of Argumedo‘s men at San Pedro and place them along the line to protect it while the train went to repair the bridges. Up to noon Sunday nothing had been heard from them. Mr. Wolff occurred permission from the officer in charge of San Pedro to send men out on a car to trest with the rebels when they ran into their territory and thereby arrange for our trip through their territory. When this car, in which Mr Williams and Mr. Carver, caught up with the train which had gone out Saturday, the officers of the military train refused to report their pass, which was issued by their own superior, and forced them to return in front of the train, pushing the handcar thirty miles back to San Pedro. This train reported that they had found nothing wrong with the track, but that they had heard that a great army of rebels were further up the line and it would be extremely dangerous for our train to proceed.

Monday afternoon we took on two cars of road materials and started out to build the road where it was destroyed and go to the border.

We built three bridges, taking up the material of each after we passed over to be used for the next bridge.

The train reached Pomona about dark and side-tracked for the night.

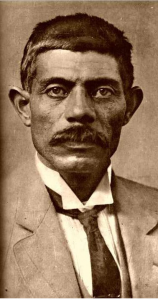

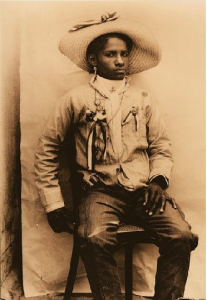

During the afternoon we had seen dust in the distance which might indicate the rebels, but we finally decided that the dust was from the animals in the distance. About 3 o’clock at night Mr Wolff came through the train and reported that the rebels were coming and that all the men whose wives were in the Pullman could go into that car. A man came to each car, but quietly asked for the conductor. A tremor of fear ran through the entire train at the news of the rebels, but a sigh of relief quickly followed when their peaceable attitude was marked. They arranged for a conference early the next day between Mr Wolff and General Robles, in charge of the rebel forces at that place. General Robles* told Mr. Wolff that our train would have to return to San Pedro.

She gave as her reason for this order that General Carranza was cut off on the main line ahead of the and that General Aubert was also on the main line in front with 1500 soldiers, $2,000,000 in money and 115,500 worth of merchandise for Torreon. If our trains went over the line it might give these men (federals) a chance to reach Torreon before the rebels could take it and thereby save the city from the rebels. She said that when we returned to San Pedro that all the federals would have been withdrawn from there to Torreon and that Torreon would be attacked that night and within three days the city would be in the rebels hands.

A large company of rebels were seen and some shots fired which hurried the action of the refugees as that we had to return and built and destroyed by is on the preceding day.

The train arrived back at San Pedro Tuesday afternoon to await the action of the rebels. Tuesday night the rebel fores made the attack on Torreon, which was immediately telephoned to us.

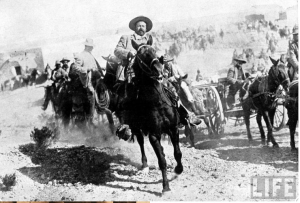

This 1914 photo courtesy of the LIFE magazine photo archive on Google shows Mexican General Pancho Villa riding with his men after victory at Torreon

The next morning the grenading? was so heavy that the phone could scarcely be heard. Wednesday night about 9 o’clock the city was taken by the rebel General Villa, and at once taken possession of enemy forces and a loan of $5,000,000 placed on the city.

The refugee train remain in San Pedro from Tuesday till the following Saturday, a city of 20,000 people, with not an office of any description open and not a policeman or officer of the law in the city. All was as quiet as one would wish.

*Colonel Carmen Amelia Robles, an Afro Mexican woman who was a leader in the Mexican Revolution. Legend has it that she participated in many battles and that she would shoot her pistol with her right hand and hold her cigar with her left.

Refugees Remained

The refugees remained at San Pedro waiting. The passengers became very much dissatisfied with the management, for no one could say the reason for not going. Hard things were said and conditions were drifting toward ???. Friday all of the trains of General Aubert and General Carranza with all the mentioned soldiers and supplies came into San Pedro on the way to Torreon without knowing that Torreon was already held by the rebels. All their plans had to be changed, and, as Torreon was the headquarters of that military route. The superior officer of all that ??? were wading in the mud with his followers straggling along behind and was not accessible to these train officers.

Saturday, October 4, the feeling had grown bitter against the management for not starting on the trip. A fist fight was narrowly averted where an Englishman gave a needless insult to an American, the Englishman defending the management. Instructions were given that we were in imminent danger that the manager of the train thought best to keep from the public. Mr. Wolff offered to resign, leaving the train at the mercy of the rebels, still Mr. Corothers could come from Torreon and appointing another to act as his representative. Pressure was brought to bear on Mr. Wolff and he finally agreed to remain at the head of affairs, but the act of not leaving with the train would be only after a conference in, which all the men would be present, where he would place before them certain well-founded rumors that had come to him at San Pedro.

About 11 o’clock Saturday morning all the men on the train were invited to meet in a baggage car and hear a report of the conditions as they were seen by Mr. Wolff.

Mr. Wolff stated that rumors had come to him from people in whom had confidence that when the train left San Pedro it would be blown up with dynamite and all on the train killed. Another rumor, equally as well founded, was that on the previous day mass meetings were held in San Pedro and that the citizens there (rebels) had planned to kill all the people on the train at night. The reasons given for these threats was to invoke American intervention. It was to be done by the rebels.

Go at Once

Mr. Wolff stated further that the last talk he had with Mr. Corothers by phone, Mr Corothers had finished the talk after a few words had passed by saying: “The rebels are now in my office and are greatly ??????? If you can get out of San Pedro, go at once”

As soon as Mr. Wolff had finished a hurried discussion, it seemed that there was nothing to do but start- even if we were blown up.

San Pedro and Torreon were both in rebel hands, and if they were our enemies, or if they sought to kill their friends in order to force intervention there was no safety so long as we were on their territory. A vote was taken as to whether we should start at once, and it was unanimous to start to Monterrey at once. In an hour the train was trailing slowly behind eleven federal trains toward Matamoros where we would have a clear track to Monterrey.

When the trains had proceeded about 20 miles the train in front stopped on a hill that crossed Lake Maryan. As they were on the main line the refugees train must needs also stop and remain there till the federal trains moved up.

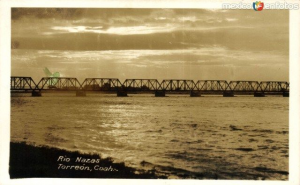

This lake is formed by the Nazas river emptying water in a low land with no outlet. When the rains are heave this becomes a large body of water, but much of the time it is dry land. At this time the lake was about 25 miles long and 12 miles wide.

As the train rested on the bottom of the lake after the sunset had drawn a rich curtain of gold studded with the silver crescent of the moon, as if nature had drawn her canopy to shut us in from the outside world, little Diantha Mayran Lancaster was born in the hospital car on the rear of the train. Dr. H.G. Schmidt and nurse, Amelia Chlaum, being in attendance.

A bottle of the lake water was obtained by Mrs. Tlistor and sisters to be used in christening the “Lady of the Lake.”

Her romantic entrance in the world centered the interest and affection of all on the train on the hospital car, and nothing was lacking that our surroundings could supply.

Terrific Explosion

Early Sunday morning while the train still stood on this lake three boxes of dynamite were carried from the federal train just in front of us and placed under a double span stock girdered bridge just 140 feet behind or train, and the terrific explosion tore the bridge to stems and threw dirt and stones on our train. The middle pillar of concrete and three of the heavy steel girders were sent out of sight under water, thereby making it impossible for the rebels to come from Torreon and capture these military trains.

About 9 o’clock the same morning, the trains in front moved out and the refugee train followed. About 20 miles was made when we came to a stop. All day Sunday the train bearing the American flag was forced to stand on the south line and wait the pleasure of the trains ahead.

About sunset on that strange anxious Sunday our train was ordered to go back to a siting at Pomona and leave the cars there while the engine took a flat car back several miles to pick up some cannons which were being brought over by the federal from Torreon. The engine again pulled our train out on the main line and some distance up the track with the flat car of cannons in front. Then our train was ordered to “back” – as we went back to straggling soldiers who had marched five days with almost not food or rest met out train and kept constantly jumping on our train with their guns and ammunition.

It was night and we were going toward a possible attack from the rebels. Mr. Wolff did not know where we were going or who had given the order to go back.

We were carrying a load of cannons in front of our engine, armed soldiers on the cars, and if we had run into the enemy a very probably thing is the flag could not have been seen and the rebels would have opened fire on our train and given the federal trains time to get out of the way.

During this trip back, Mrs. Latona and family, who had left Torreon with the federals after walking from their home to Matmoras, 15 miles, barefoot, caught our train and were taken in and given every necessity. Mr. Latona is a leading lawyer in Torreon and no one stands higher, either socially or professionally, than does this family. While hundreds were in this company, and had walked for days with scarcely and food, the first thing asked for was cigarettes. The refugee train finally stopped for the night within a few miles of where it spent the night before

Baby Dies on Train

Sunday night a baby died on the train and was buried Monday morning about 6 o’clock in the prairie about 280 feet northwest of ????? No 647.8. The baby was only a few months old, and the child of German father and Mexican mother. Alone in the desert where the wild coyotes howl, love built a little mound and left a little body to sleep awhile.

Monday morning some of the ladies of the American train sent a nice lunch to General Bravo, who came with the federal the day before form Torreon.. The general had been in military charge of the city for six months and had many friends among the Americans. Mrs Ed Wolff, Mrs Corothers and others sent a lunch of sandwiches and fruits to him and General Manguler, who was in charge of the city when it was evacuated. They told a touching story of the days they had traveled since leaving Torreon with nothing to eat except the buds of the cactus and for drink they were forced to resort to certain herbs which contained water. General Bravo cried like a child at the kindness and ordered all the ladies “una abrazada” (a hug)

During the afternoon of Monday, October 6, our train was getting into a state of anxiety. We could have no way of passing those eleven federal trains and to return to San Pedro was impossible. Mr. Cunard Cummins, being a personal friends of some of the military officers General Bravo, was sent by Mr. Wolff to arrange with the federal officers on these trains for us to pass. He was courteously received and admitted that anything in the realm of the possible would be done to relieve our train and let us pass.

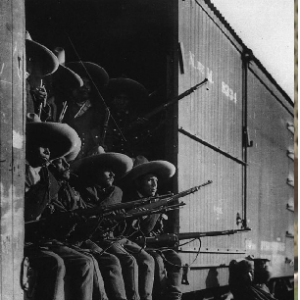

Found on thisinsignificantlife.tumblr.com

Just at this time the trainmaster of these trains came in and said that of the eleven engines, eight of them were dead and it was impossible to move the trains. The officer told Mr. Cummins that they would go to the temporary telegraph office and get in touch with Monterey and report the condition of the refugee train. As they approached the office the operator saluted and regretted to report that at the minute the wires had been cut, which not only made it impossible to get Monterrey, but mad it exceedingly dangerous to start in that direction, since it was an indication that a large band of rebels were on the road and would rob and silt.

All Prearranged

Mr. Cummins returned and reported that he thought all was prearranged and that we were held for some purpose and he had no hopes of getting out by the consent of the federals. We were nearly out of wood and water for the engine, food was out for the passengers, except some rice and beans and we had at least six people on the train that could not eat this except at great risk. Some we were fearful would die before the train could get through, even with no unnecessary delay.

Having been in this position for three days and nothing being accomplished except to finish the poor fare and wait the ravages of the tireless trackless prairie. Mr. Wolff determined to do a daring think. He sent a handcar to Monterrey with six Americans on it in charge of Mr. Richardson and with two of the Drew boys to report our condition to Consul General Hanns. We had sent out three handcars before and all of them had been picked up by either federals or rebels and came to nothing. If this one failed there was nothing further to do but wait and starve. When the passengers went to the cook car they were shown all the bread that remained. It had been cooked before we left Torreon, nearly three weeks ago. It had been picked over till what was left was green with mold and rot. Nothing could be secured except a little rice, which the men cooked in any vessel that came to hand over a tiny fire kindled along the railroad track.

The Americans on our train waited in almost hopeless expectancy. The passengers droned in dull tones as they tried to express a hope that was little felt. Fathers looked into faces that were pinched with hunger and heard for the first time in their lives their own children cry for bread when there was none to give.

We had been promised food and other supplies by the federal trains in pay for out going for their cannon and taking some of their tired refugees. Nothing came of these promises. There was nothing to do but wait, and we waited.

Skeletons of Wrecks

Tuesday night we saw the engines of these trains that had dead engines begin to smoke up and get ready to move, and before long we were notified that these trains could be sidetracked at Tisook and Madero, and that it would be possible for us to get by them. We followed as fast as they cleared and passed over road/bed fresh built from the former wrecks. We saw on every siding and even along the main line the skeletons of burned cars and locomotives and the charred remains of every station along the line. Coming at last to the stations where we had expected to pass these trains we were almost surprised to see that one hope at least had been realized and one promise of the federal officers had been fulfilled. During the night we passed all these trains and found an open road ahead of us to Hipollito.

The six Americans on the handcar had got in touch with the consul general when the trains found that they could give us an open road. Just what was officially done is known only in official circles, but we could but believe that there was a voice heard from across the line with a limit to the time that rain could be held in that stranded condition.

When the refugees reached Hipolito there was nothing to eat. Not even bread. A man with three children and a sick wife was seen to buy three ears of green corn, give one to each of the two children, old enough to eat, and taking the other himself ate them with the joy of the first fruits of the harvest. An Indian woman cooking tortillas, many corn hoecakes, which had been bought regularly for half a cent each, netted 25 cents each, and her supply could not satisfy the demands for them.

We left Hipolito about 12 o’clock Wednesday for Monterrey. When we were about twenty miles on the way we met a relief train which had been sent out by Consul General Hanns on first hearing of our plight. This train had more good things to eat on it than any train these refugees ever saw.

Dr. Ryan and Rev. Jackson B. Cor of Monterrey, were in charge. They came through the train supplying everybody that smoked with cigars and cigarettes and reporting that there would soon be food in the cook car. One of the passengers from the rear car went to the cook car, which was in front and secured a loaf of bread which looked to be a yard long. Holding this in a conspicuous way he went the length of the train with the first piece of good bread these folks had seen for two weeks. Soon the transfer of fruit, bread, milk, meats and ice was made to our train and we knew the road was open to Monterrey and that the wires would soon tell those we loved and had heard nothing from for four months that we were out of the danger zone.

The joy of that ride to Monterrey can only be felt after the trying experiences of the fourteen days since we had left Torreon. The mountain whose heads towered above the clouds as they whispered of the Creator shamed us for ever having a fear and we felt that “the angels of the Lord encamp round about them that fear Him and deliver them.”

About 5:30 o’clock we reached Monterrey and the station was filled with friends willing to do anything to make us feel at home. Anglo-Saves met Anglo-Saves in a foreign land and they loved each other and they offered the weak their strength. As must be cared to leave the train were some housed in hotel, hospital or private-home for the night. All expenses of all the Journey from Torreon to their home in the states was borne by the Red Cross Society through the state department of the United States government.

** I found an ebook with an excerpt of this story. It is the Missionary Voice vol 3. Here Rev. Lancaster is describing the situation in Torreon in a bit more detail. He is thankful the city is still in the hands of the Federals. Food is scarce but he is anticipating relief trains from Mexico City. His children are sick with Scarlet Fever and his pregnant wife is in bed with fever and exhaustion. As he asked for prayers, he admits little church work is being done at the time but ends with the notion that “Faith begins each day (with) its sufficiency of grace”

Follow

Follow